This section provides information on how you can submit a Communication to the African Commission to complain about a violation of the rights protected by the African Charter. It follows from Section 2.7 Communications Procedure – Why are they useful?

You can learn more about the Communications procedure in the African Commission’s information sheet on the matter, which you should read beforehand.

Before submitting a Communication you should analyse past decisions and check if a case with similar facts has already been discussed or if it is a recurrent theme, because past decisions can be cited in support of your own case for the African Commission to rule accordingly. An important tool is the African Human Rights Case Law Analyser (‘Case Law Analyser’), created by the Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa (IHRDA), based in Banjul. It is one of the best sources of African Commission case law, including decisions on Communications, as well as other documentation like judicial decisions by the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, based in Arusha (Tanzania), and decisions by other committees.

An individual Communication can be brought forward for a right violation by either:

A Communication must be submitted in one of the AU’s working languages, which are English, French, Portuguese, Arabic, Swahili and Spanish.

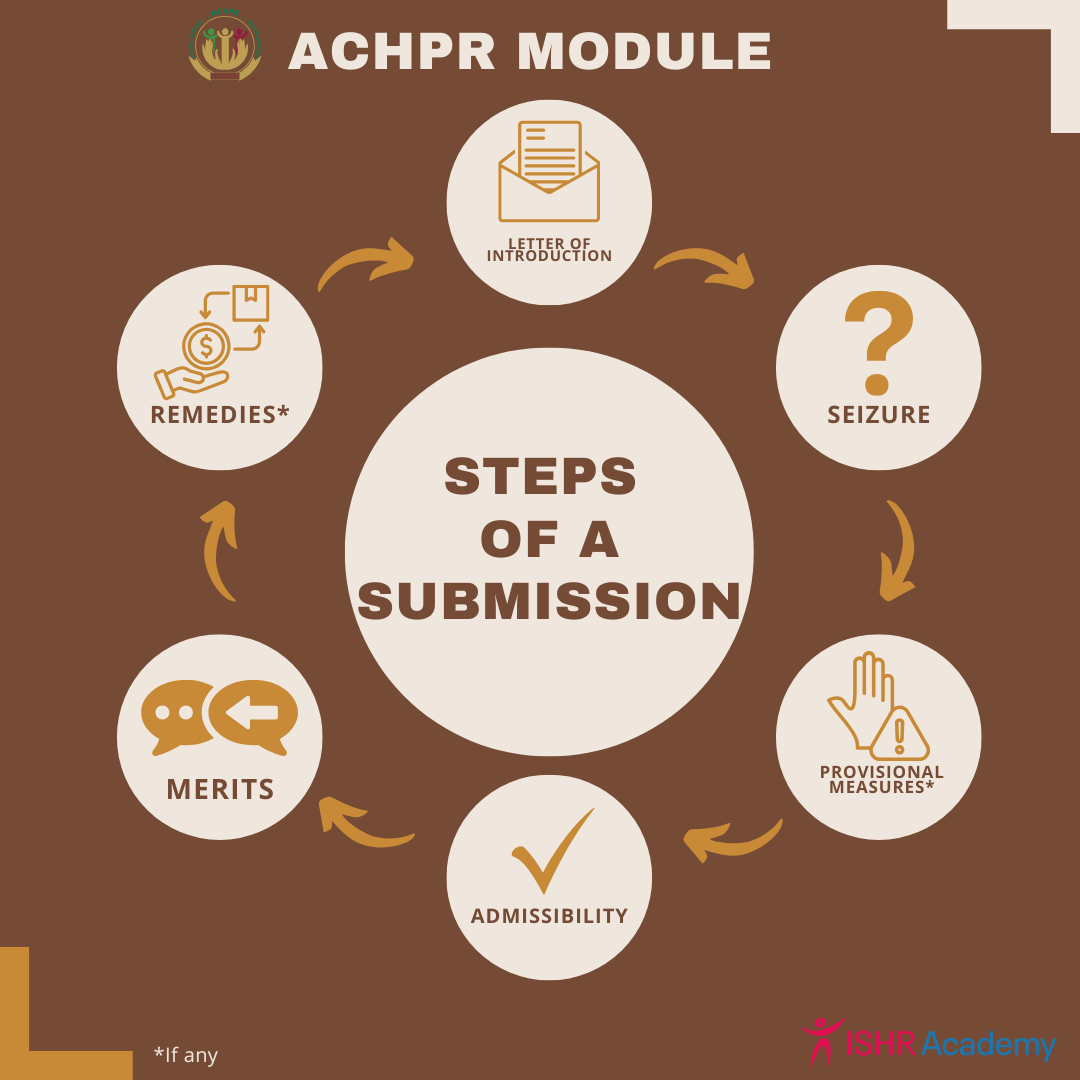

See below for key steps and tips regarding the submission of a Communication :

A letter of introduction is an initial complaint sent by the complainant(s) to the African Commission. It includes a brief description of the facts, the attempts made to exhaust domestic remedies, and contact information. This letter may be sent by email at [email protected] or by post to the ACHPR Secretariat in Banjul (The Gambia). It is advisable to follow up with the African Commission once you’ve sent your Communication to ensure that you get a confirmation of receipt on their part.

Once the Communication has been duly received, the African Commission will decide whether it will consider the Communication (called the ‘seizure’). At this stage, the African Commission will initially look at whether the Communication is signed, whether it is directed at a State party to the African Charter, and whether there is a prima facie (‘at first sight’ or ‘based on first impressions’) violation of the Charter. If the African Commission decides to consider the Communication, it is officially ‘seized’ and will inform the State party in question of the Communication against it.

The African Commission, at any point in the process, and once it has been officially seized, can issue provisional measures to ‘prevent irreparable harm to the victim or the victims of the alleged violation as urgently as the situation demands’ (Rule 98 of the Rules of the Procedure). This can take the form of an order to the State party concerned, for example to protect the life of an alleged victim. However, it is important to note that an indication of provisional measures is not a decision on merits. It exists to allow for the African Commission to have time to make a decision based on merits, which comes later.

Once the African Commission is seized of the Communication, the complainant has two months to present evidence and arguments on the admissibility of the case. There are seven criteria for a Communication to be admissible, and they must all be met; they are:

With respect to evidence, it is important to ensure that all allegations are well-supported and based on specific facts; the more concrete and specific evidence you provide, the better. This can include: testimonies/affidavits, expert opinions, medical/psychological records, photographic evidence, reports by international organisations or NGOs, judicial decisions, etc. As documentation can get lost, it is advisable to send documents electronically in addition to mail. Moreover, make sure to explicitly specify which provisions of the African Charter are violated for each allegation, as well as conduct a thorough research of the jurisprudence of the African Commission on those rights. A Communication must address specific violations of rights, not simply the general political or security situation in a given country.

Once a Communication is declared admissible, the African Commission will seek to facilitate a friendly settlement and will appoint a rapporteur to facilitate such a friendly settlement, usually the Commissioner who has been handling the case so far. If a friendly settlement fails to be reached, the Communication will move to the ‘merits’ stage.

If a Communication is declared inadmissible, the complainant can reintroduce the Communication.

Once the Communication has been declared admissible and moves to the ‘merits’ stage, the State party has 60 days to reply with its own submissions, followed by another 30 days for the complainant to respond in return. To determine the merits of the case, the African Commission will apply the African Charter and general international human rights law standards and principles. Finally, in determining the merits of your Communication, the African Commission offers the parties the possibility to request a hearing. This can allow you to present your case before the African Commission directly, but it may also add more time to the processing of your case and will also incur additional costs to travel to Banjul.

If the African Commission rules in your favour on the merits, it may order different kinds of remedies, which will depend on the nature of the violation, for example: restitution (restoration of liberty, citizenship, residence, property, etc.), compensation (financial), rehabilitation, satisfaction (procedural, for example ordering a re-trial, an independent enquiry, an official apology or recognition, etc.), guarantee of non-repetition.

Remember that it is not unusual for the State to ignore Communications, refuse to cooperate, and refuse to comply with the African Commission’s final recommendations. So while the African Commission can and does follow up on the implementation of its decisions, it does not have the power to compel a State to comply. As such, it is up to you to ensure you have an advocacy strategy in place to push for compliance and full implementation back home.

Steps and timeline of a Decision made on a Communication for a litigant, or a complainant (Equality Now)

Article 59 of the African Charter provides that the proceedings relating to the Communications procedure of the African Charter shall remain confidential until the AU Assembly decides otherwise. This has historically been interpreted quite restrictively to prevent any discussion of the proceedings surrounding a Communication.

As such, bear in mind that, if you choose to submit a Communication, you will not be able to share, publicize, discuss, or otherwise mention the submission and progression of the case at all throughout the entire duration of the process (several years). Only the Communication decision will be published by the African Commission itself, which you will then be allowed to discuss, but only at the very end of the entire process. There is currently a campaign to get the African Commission to interpret Article 59 in a progressive spirit in line with the right to access to information, see here and here to learn more.

In Kenya, the Ogiek community faced a grave injustice when they were forcibly evicted from their ancestral lands in the Mau Forest, one of the last remaining habitats for forest dwellers. In November 2009, the Ogiek Peoples’ Development Program, in collaboration with the Centre for Minority Rights and Development and Minority Rights Group International, took a stand against this violation and submitted a complaint to the African Commission. The complaint detailed how the Kenyan government had violated numerous rights outlined in the African Charter, including the rights to freedom from discrimination, life, development, property, control over wealth and natural resources, culture, and religion.

In 2012, the African Commission transferred the case to the African Court, making it the first time this ever happened in the history of the African human rights system. Then, in 2017, the African Court issued a landmark ruling confirming that the Kenyan authorities had indeed infringed upon the rights of the Ogiek community, along with other rights protected by the African Charter. Five years later, in 2022, the African Court took a further significant step by ordering the Kenyan government to provide reparations to the Ogiek people for the moral and material harm they had endured. Additionally, it mandated that the government officially recognize the Ogiek as Indigenous Peoples, marking a crucial victory for their rights and identity.

In December 2014, human rights defenders Farouq Abu Eissa and Dr Amin Mekki Medani faced an alarming ordeal when they were arbitrarily arrested in their homes by the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS). Their detention lasted over four months, during which they endured mistreatment and were charged with unfounded offences. As news of their plight spread, several civil society organisations sprang into action. In February 2015, groups such as the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS), the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), and REDRESS filed a Communication with the ACHPR. They called on the Commission to demand the unconditional release of the two defenders, which they obtained the same year, as a significant win. The ACHPR issued provisional measures, compelling Sudan to ensure that both human rights defenders received medical care and legal representation.

In November 2022, the Commission reached a significant conclusion, determining that Sudan had indeed violated the rights to personal liberty, fair trial, free expression, and freedom from torture. The Commission ordered the Sudanese government to provide adequate compensation to the defenders and to launch a prompt investigation into the abuses the defenders had suffered.

As per Rules 104 to 107 of the Rules of Procedure, a third party may intervene in a Communication procedure before the African Commission. This is known as an amicus curiae (literally ‘friend of the court’) and may either be directly invited to intervene by the African Commission or request to do so. Click here to discover how you could be involved and what it entails.

See the next sections on how you can engage in other aspects of the work of the African Commission, including country visits.